The penultimate episode of Cosmos, “Encyclopaedia Galactica,” is about the search for extraterrestrial life, as well as how we might communicate with that life. This episode is also in the recursive mode of the earlier half of the series—it begins with the Barney and Betty Hill abduction story and a refutation of UFO theories, moves to Champollion and the Rosetta stone, and then shifts to a conversation about potential interstellar communication and the civilizations that just might be trying to do that communication. This all comes back, of course, to the problem of the UFO and the reasons why we’ll likely hear communication from far away before we see anyone visiting our skies.

It’s been a long time coming in Cosmos for Sagan to discuss extraterrestrial life directly and with an unwavering focus. We’ve done a lot of speculation and thought-experiments, throughout, but haven’t talked much about the cultural narratives we have about extraterrestrials and their potential veracity. It makes a certain amount of sense to me that this—the most obvious, clamoring topic—is kept for the end; we’ve been leading up to the discussion for many hours, now. And I also think it’s good, effective, that the series has done so much work to explain the scientific thought process before diving into a topic where healthy skepticism is for the best. This tactic also lends legitimacy to a topic that some might scoff at—after all, we’re doing science here, too.

“What counts is not what sounds plausible, not what we’d like to believe, not what one or two witnesses claim, but only what is supported by hard evidence, rigorously and skeptically examined. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

This is the major point Sagan makes in his discussion of extraterrestrial life, particularly in terms of whether or not any of that aforementioned life has been touching down on Earth to visit. Though he’d like to believe—I can already tell I’m going to have to try very hard not to make X-Files jokes in this post—he must find the evidence, first. Stories of UFOs and abductions don’t stand the test of rigorous examination; it might sound harsh, but it’s true. Sagan is at turns gentle—as I noted, he does want there to be life elsewhere—and sharp, with humorous lines like: “But if we can’t identify a light, that doesn’t make it a spaceship.” Also, though he doesn’t say it directly, I do think that his comments about the human tendency to find self-fulfilling patterns throw back to the previous episode on the mind. We, as humans, are developed for intense pattern-recognition. It’s no shame that we find those patterns appealing when we think they prove extraterrestrial life. However, that’s no excuse to rely on superstition rather than science, as he points out again and again. (The first part of the episode is actually a teeny bit heavy-handed, reflecting back on it.)

And now I really can’t resist: that re-enactment of the Barney and Betty Hill abduction? I suddenly understand where the music direction came from in The X-Files. Surely, they must have watched a little Cosmos. The use of the music in this scene hearkens so directly to that show, I can’t imagine that Chris Carter and company did it by accident. Just listen to the eerie, intense echoes and sudden, sharp percussion. (Or: did Cosmos borrow this from another, earlier production? Is there a genealogy of alien abduction music?)

However, the following section on Champollion is, perhaps, my least favorite bit of the series. I understand the vital need to explain the concept and the history of the Rosetta stone to lead the audience to a discussion of science as the Rosetta stone for interstellar communication—and yet, these scenes, compared to what’s come before, seem lacking. The enthusiasm Sagan brings is lower, for one thing; for another, it does seem to throw the balance of the episode’s narrative off a touch more than the recursive scenes should or generally do. I do like one of the lines from the section (the one about the temple’s writing having “waited patiently through half a million nights for a reading”), but overall it strikes me as somewhat lackluster. Feel free to disagree—I’m curious about other peoples’ reactions to this section.

Then we get to discussions of the science of attempted communication, and it’s interesting again—though, now, outdated. What I find particularly fascinating is the glimpse back into time at the progress we hoped to make in our searches of the universe and our broadcasts out into it. Things have certainly moved forward, and died down, and moved forward, and died down again. I can’t imagine Sagan would have been pleased with the recent hubbub around cutting NASA’s SETI funding, as he certainly wasn’t when it happened in the early eighties. The context of the arguments around the utility of SETI programs is something that I think helps put this episode into its time and offers the contemporary audience a way to understand why Sagan is so enthusiastic about the programs and their (then-)expansion.

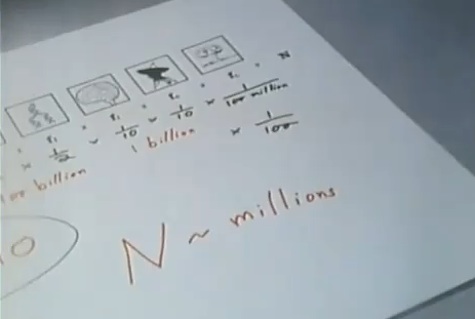

On a smaller note, I also love the little block illustrations of Sagan’s version of the Drake Equation. Of course, as he says, it’s kind of all guesswork after a point, but it’s still intriguing. Though a small thing, it also struck me that he couldn’t be sure yet if the stars in question had planets—because at the time, as came up in a previous episode, we couldn’t do much to determine that. How would Sagan feel, I wonder, at the discoveries of new planets we now make on a regular basis? Judging by the stunning end to the episode, the exploration in illustrations of the Encyclopaedia Galactica, he would have loved to have seen the planets we now know are there, across the sea of stars.

I remember, too, being struck by the pessimism of the last step of the Drake Equation. As Sagan says, we’ve only had this technical society for a few decades, and we might destroy ourselves tomorrow. That last part of the equation is the nasty part—self-destruction, which seemed increasingly likely during the era when Cosmos was written and filmed. The threat of nuclear holocaust looms smaller, now, or perhaps we’ve grown inured to it; however, it’s a damn big deal in 1980, and Sagan’s estimation that a vast, even overwhelming, number of societies will destroy themselves is sobering. However, “The sky may be softly humming with messages from the stars,” as Sagan says. If a civilization sends us a string of prime numbers, it might be a hello, not an accident—and if they can survive their technological expansion, “We also may have a future.”

We could learn from them, if they would show us their knowledge, and perhaps have a way to make it alive into our future. The implications are stunningly pessimistic, and yet, also offer a way for growth. It’s a mixed message, and one that—even today—provokes self-examination of our behavior as a species, on this planet, before we readily look outward at others. However, the closing quote pulls us back around to something a bit more hopeful, and more in the general tone of Cosmos:

“In a cosmic setting vast and old beyond ordinary human understanding, we are a little lonely. In the deepest sense, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence is a search for who we are.”

*

Come back next week for episode 13, “Who Speaks for Earth?”

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.